Michael Scott, the infamous Regional Manager on NBC’s American version of “The Office” was always getting himself into interesting situations. He always meant well, but it somehow never quite worked out the way he intended, often resulting in hilarity. When I’m commuting, I frequently recall one of the episodes where he and Dwight are traveling to a client, following their GPS for directions. For those who have seen it, you might already be smirking as you remember what happens. The short version is that Michael eventually steers them directly into a lake, because the GPS insists they should turn “right”.

While The Office may not be your go-to for life lessons, this particular moment is extremely relevant to life in the classroom. As educators, we are more often than not provided with a curriculum to support us in navigating the yearly-daily(!) ongoings of our classroom. It is meant to guide us in making instructional decisions that meet the needs of our students. We use it as a way to keep us “on track” with delivering content that will support students in subsequent years of schooling. However, even with the best of intentions; if we follow our curriculum (whether that be in the form of a textbook, a techbook, a printed bundle of lessons, etc.) with complete fidelity, we can sometimes find ourselves driving directly into the proverbial lake.

I’ve witnessed this miscalculation numerous times and experienced it firsthand as a teacher. This doesn’t look like your typical lake, yet it’s just as messy. You are met with muddied, confused looks from your students as they cling to whatever life buoy they can get their hands on. So why do so many of us find ourselves in this situation year after year? Why do we insist on listening to the GPS and turning to “Lesson 3” even when we see a lake of confused students ahead?

Pacing. Being Unaware. Self-doubt.

Heads up: There are a lot of strategies ahead. While they do work well when used in conjunction with one another, it may be overwhelming to try and integrate everything at once. So, my best advice to you is to pick ONE that feels the most exciting or relevant and try that out first. You might just notice that making one small change will lead to big shifts in your students’ learning.

Heads up: There are a lot of strategies ahead. While they do work well when used in conjunction with one another, it may be overwhelming to try and integrate everything at once. So, my best advice to you is to pick ONE that feels the most exciting or relevant and try that out first. You might just notice that making one small change will lead to big shifts in your students’ learning.

Pacing: Zooming Out

The pressure that accompanies that word, “pacing” is a real thing and it’s felt by teachers across schools, grade levels, and content areas. There are many factors that influence its intensity — standardized assessments (state, region, or schoolwide even), school culture, the newness of the curriculum/learning standards for the teacher, and access to other grade level teachers, just to name a few. But… have you ever taken a moment to step back and and think of pacing from a wider angle? It could be your ticket to staying grounded.

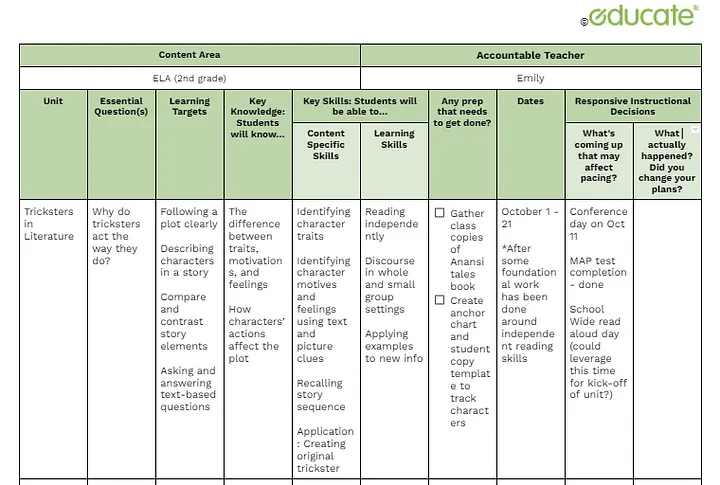

It can be a difficult thing to do, but the more we look ahead in the curriculum and understand the larger scope of learning, the more confident we will feel making the day to day adjustments. In other words, take the time to zoom out, so you can zoom in. One way to do this is to use planners like the one below. Notice how it doesn’t ask for specific lesson information, but focuses primarily on the big picture. This particular planner even pushes us to anticipate any upcoming interruptions to instruction and includes a reflective piece, asking us to think about, “What actually happened?” as a way to make adjustments for the subsequent year.

Being Unaware: Better Questioning

The saying “Ignorance is bliss” comes with a caveat. Picture this: you’re blissfully planning away the coolest lesson of your life, experiencing moments of, “Wow I am soooo creative; the kids are going to LOVE this!” Then the day arrives to actually kick it off in your classroom and you quickly realize that your bliss was short-lived, an unfortunate result of your incomplete picture of students’ existing misconceptions. It’s happened to all of us at least once, but I’m here to tell you it’s avoidable and that awareness is bliss.

At Educate, we often support teachers in integrating instructional practices that ensure what we call, “Co-creation of Knowledge” (CCK). CCK in its fullest form is defined as: Teachers effectively facilitating discussions and activities in which learners are incorporating their own ideas and misconceptions to create knowledge. In other words, teachers are not the “keepers of knowledge”, but facilitators of discussion in which they have more opportunities to authentically hear from… their students! One of my favorite practices associated with CCK is the use of generative questions — primarily asking open-ended questions to all students in the classroom in order to support processing and gain a deeper understanding of their misconceptions.

Not sure if you’re asking generative (open-ended) questions? Here are some clues that you may have a tendency to instead rely on close-ended questions and are in need of a change:

- It takes students very little time to craft a response to your questions (even during a “turn and talk”)

- Students are answering with one-word responses

- You can predict exactly how a student will answer your question

- Your question-answer cadence feels a lot like a game of ping-pong between teacher and student and back again

- (And my personal favorite) There is only one right answer to your question

If any of those sound familiar, it may be time to switch up your technique.

Self-doubt: Data Listening

Rather than allowing our self-doubt to be paralyzing, let’s instead explore how we can use it as a motivator to become expert data collectors. What exactly do I mean by this? Many teachers feel uncomfortable making course corrections during instruction. They quite literally “go by the (text)book”, because they either figure it was written by a group of experts and it should be followed, or they were told to follow it. This is the same kind of thinking that leads us directly into the lake. So instead of this mindset that keeps us looking and moving in the same direction no matter what, let’s engage our other senses to course-check and course-correct.

If you adopt the practice of asking generative questions, you will suddenly find yourself inundated with data galore. Just the simple act of listening closely will help you to hear cues that indicate the need for course correction — whether that be moving forward, or turning to take a slightly different approach. However, this skill doesn’t always come naturally. With the busyness of a classroom, it can be hard to sift through what you’re hearing and decipher exactly what it means. In order to build this muscle, teachers can engage in these two practices.

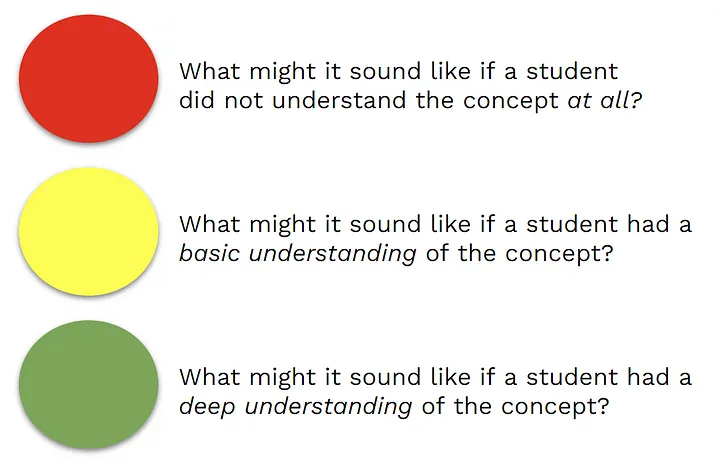

- Pre-instruction: Remember those generative questions you spent time planning? Take a moment to anticipate student responses. I like to use a simple “traffic light” approach like the one pictured below. This approach is great, because you can even take it a step further and plan follow-up/scaffolded questions to support students on the spot.

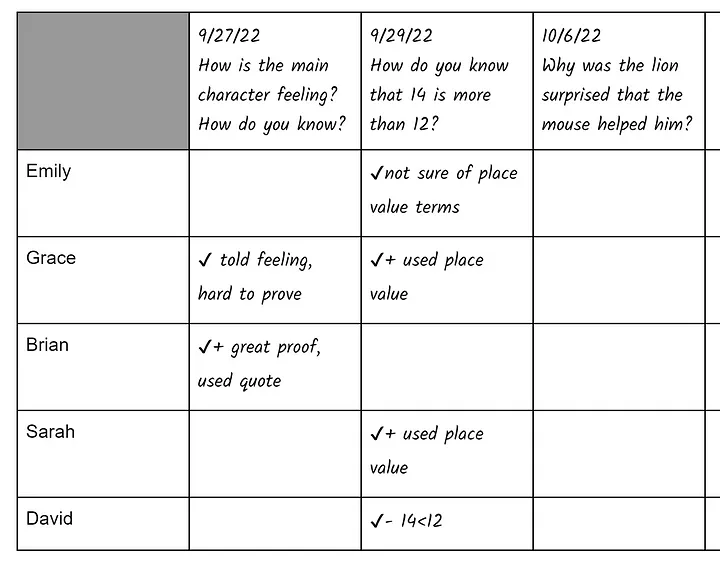

- During instruction: Rather than trying to memorize everything your students say during instruction, implement a system like the one pictured below to easily (key word, easily) record student responses to your questions. Not only will this help you adjust instruction, but it will also be great data to pull on for your next progress report or conference. Note the use of a check +/- system to make it even more efficient.

Course-correcting can seem like an overwhelming task when paired with our other responsibilities as educators. Classrooms are busy places and we often find ourselves taxed beyond our capacity, wearing “blinders” in order to survive. While we may feel like this narrowed view is helping us, it’s actually hurting us in the long run, preventing us from making the necessary adjustments to support our students. So instead of simply “turning right” next time, take a moment to glance up, look around, and make an informed instructional decision.